Frequently Asked Questions on Assembly Bill 191

This FAQ on AB 191 addresses questions and corrects misperceptions of AB 191.

What is AB 191?

Assembly Bill 191 would establish regulations for collective bargaining for NSHE professional employees in Chapter 288 of the Nevada Revised Statutes, similar to those for local government employees and state Classified employees (including Classified staff at NSHE).

Where is AB 191 in the legislative process?

AB 191 had its first hearing in the Assembly Committee on Government Affairs on March 5, 2025. The next step is a work session to vote the bill out of committee. It is then expected to be re-referred to the Assembly Committee on Ways & Means for consideration of fiscal issues.

Update: AB 191 was passed by the Assembly Committee on Government Affairs and has been re-referred to Ways & Means for a fiscal hearing. It is exempt from deadlines.

Don’t NSHE faculty already have collective bargaining?

Since the mid-1970s, the Board of Regents has allowed collective bargaining for faculty under its own constitutional authority. However, Title 4 Chapter 4 (T4C4) of the NSHE Handbook has not had a major update since 1990 and it has not kept up with changes in collective bargaining statutes for other public employees in Nevada. It also does not match current practices for the existing faculty collective bargaining units at CSN, NSU, TMCC, and WNC. For example, T4C4 states there is a single bargaining unit for the community colleges, but de facto there are three separate negotiations and three collective bargaining agreements approved by the Board of Regents at the three community colleges with faculty bargaining units.

Couldn’t the Regents just update Title 4 Chapter 4 of the Handbook?

In principle, yes, but NFA has been seeking revisions to update and modernize T4C4 since 2022 to no avail–the proposals have not even been agendized for Board discussion. Regardless, only the Legislature can authorize important pieces of the provisions for collective bargaining and labor relations that other Nevada public employees have in NRS 288; for example, access to the state Employee-Management Relations Board for efficient resolution of disputes over contract provisions. T4C4 currently limits conflict resolution to fact finding and mediation while AB 191 also provides for arbitration. We see expanded conflict resolution options as positive. AB 191 creates a level playing field for negotiations between professional employee associations and management.

Would AB 191 expand the number of NSHE employees with collective bargaining agreements?

Not by itself. AB 191 provides the framework for organizing bargaining units, the first step toward negotiating a collective bargaining agreement. With AB 191, groups of professional employees with a shared community of interest could come together and ask for recognition and for NFA or another employee association to represent them.

Would AB 191 increase the number of NSHE employees with collective bargaining from 930 to 22000 (as implied by Deputy Counsel Carrie Parker at the March 7th Board meeting)?

No. The current number of NSHE employees eligible to form bargaining units includes 2500 Classified employees, 3200 full-time academic faculty, and about 4000 full-time non-managerial administrative faculty (total of about 9700 employees). Under AB 191, the additional eligible employee groups would include about 2400 graduate assistants, 550 postdocs and medical residents, 53 DRI technologists, and an unknown number of part-time instructors (LOAs) and hourly workers who work over 160 hours per year (more than one 3-credit course for LOAs). The 22000 number quoted by NSHE is an exaggeration–it appears to be the headcount of all NSHE employees other than Classified staff and Executives, including part-time and temporary workers who would be excluded by AB 191.

The number of members of the current faculty bargaining units at CSN, NSU, TMCC, and WNC is about 870. The new bargaining unit at NSU adds 126 academic faculty, for a total of under 1000. That is, 33 years after the first faculty bargaining unit formed at TMCC only 14% of the eligible 7200 faculty employees have chosen to form bargaining units by a majority vote.

By their nature, collective bargaining agreements are collective, group contracts, not individual faculty contracts where the workload would scale with the number of employees. So although 1000 faculty are members of bargaining units, there are only four CBAs to be negotiated and managed.

How would the number of NSHE employees with collective bargaining agreements increase with AB 191?

By itself, AB 191 does not increase the number of collective bargaining agreements from the current four at CSN, NSU, TMCC, and WNC, with a total of about 1000 faculty members in those bargaining units. New bargaining units would first have to be established under the rules of AB 191, then negotiations would ensue leading eventually to new agreements.

How many new bargaining units are likely to form under AB 191?

Beyond the four current faculty bargaining units at CSN, NSU, TMCC and WCN organized under the T4C4 rules, Graduate Assistants represented by the Nevada Graduate Student Workers-UAW union are seeking recognition. Graduate Assistants are asking NSHE to ‘count their cards’ showing their super majority. Organizing any units beyond those will be a deliberative and democratic process, often taking a few years.

Even in the unlikely scenario that all eligible professionals chose to organize, the total number of bargaining units would likely be fewer than a dozen bargaining units. Some employees are challenging to organize, some might not want to. The principle we hold is that all employees should have equal rights and equal terms. AB 191 rationalizes and simplifies the process not only for workers, but for NSHE, too.

Because Section 25 of AB 191 establishes a presumption that academic faculty bargaining units will be formed within each institution, there are four additional possible academic faculty units (DRI, GBC, UNLV, and UNR academic faculty). Other occupational groups such as Graduate Assistants would presumptively have a single bargaining unit statewide, but ultimately the membership of bargaining units results from consultation between NSHE and the professional organization seeking to be designated as an exclusive representative.

Can’t UNLV, UNR, and DRI help graduate assistants (GAs) without allowing them to collectively bargain?

The power imbalances and resulting mistreatment reported by graduate assistants are best addressed through collective bargaining, giving GAs input in their workplace policies. Only recently have institutions provided any due process for terminating GA positions; NSHE Handbook policy is mostly silent as it relates to GAs--there is no grievance process for them. Allowing GAs to collectively bargain ensures that everyone (GAs and their supervisors) know their rights and responsibilities and hold to them. A supermajority of GAs at UNLV, UNR, and DRI have requested recognition of their union for collective bargaining.

Do Nevada Revised Statutes currently allow NSHE to collectively bargaining with (a) faculty and (b) graduate assistants?

Yes. Under NRS 396.110 and 396.280 as well as its constitutional authority, the Board of Regents can and does collectively bargain with faculty employees, as provided in Title 4, Chapter 4 of the Board of Regents Handbook.

NRS 396.251 exempts NSHE from nearly all statutes related to personnel for student workers (which includes graduate assistants), postdoctoral scholars, and medical residents. That means NSHE is not bound by state personnel law and is free to recognize an association of graduate assistants and collectively bargain with them. Title 4 Chapter 4 would simply need to be revised by the Board of Regents to include graduate assistants as a bargaining unit.

However, only the Legislature can provide for certain aspects of collective bargaining; for example, access to the state Government Employee-Management Relations board by employees and governmental employers for resolution of issues regarding formation of bargaining units, negotiations, and contract compliance. AB191 provides the same rights and responsibilities for NSHE professional employees that other Nevada public employees have. AB191 would also ensure the rules of engagement for collective bargaining would not be entirely under the control of management, an apparent conflict of interest.

How does collective bargaining work for tenured or grant-funded faculty?

All academic faculty share most working conditions and employment policies, but with different contract termination provisions for tenured, tenure-track, non-tenured-track and grant-funded faculty members. A negotiated collective bargaining agreement can take those differences into account and provide appropriate due-process provisions for all. A collective bargaining agreement bolsters, rather than replaces, shared governance and peer review processes--which would remain in place for academic faculty. For public colleges and universities with faculty collective bargaining units, it is common for negotiated provisions about tenure procedures to be limited to permanent state-funded positions, for example.

Does AB 191 increase the compensation and benefits of professional employees? How would that be funded?

Not without mutual agreement in a collective bargaining agreement (CBA). Compensation and benefits are a topic of negotiation for CBAs, but any compensation approved that requires new state appropriations for implementation would be a budget request by NSHE through the regular state budget process. Such provisions would not go into effect unless and until the state funds are appropriated. The Governor is not required to include funding of collective bargaining agreements in the Executive Budget, and the Legislature is not required to approve them. However, NSHE and the employee association could to to the Governor and Legislature with a united message to implement a collective bargaining agreement.

Important cost-free policies and procedures can be negotiated in CBAs to improve working conditions and the efficiency of the colleges and universities. Studies show that institutions of higher education with faculty unionization have lower costs and better student outcomes. The current CBAs at CSN, TMCC, and WNC are available for review at https://nevadafacultyalliance.org/page-1464388 .

How much would AB 191 cost NSHE to implement?

NSHE’s fiscal note claims it would need to hire 20 new staff including seven new labor attorneys to implement AB 191, but at the three current bargaining units at CSN, TMCC, and WNC, negotiations have been handled by existing administrators and human resources staff. Since NSU's bargaining unit has already formed under T4C4, AB 191 does not add to the cost at NSU. In the Labor Relations Unit of the Office of the Attorney General, two attorneys handle collective bargaining negotiations and litigation for the 12 statewide bargaining units for Classified employees represented by five employee associations. NSHE's fiscal note for AB 191 is a gross exaggeration of any realistic needs. NFA has prepared a full analysis of the fiscal impact of AB 191, including a recommended appropriation for reasonable expense.

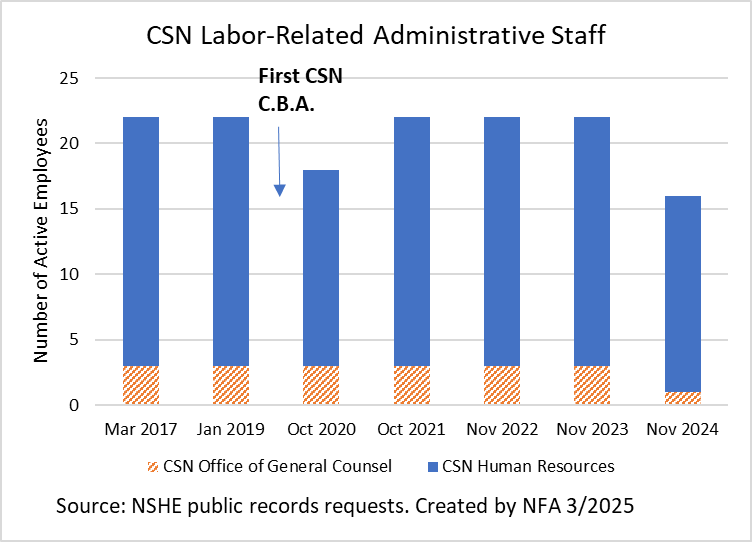

After CSN faculty negotiated their first CBA in 2019, the labor-related staff in CSN legal and human resources departments did not require an increase in positions–although the responsibilities of some positions may have shifted for different processes under the CBA.

The NFA supports appropriations to cover reasonable costs of implementation. AB 224 in 2023 included appropriations, but was vetoed by Governor. It would be reasonable for NSHE to add a labor attorney and a labor relations specialist at the system level to provide support for the institutions and to handle an additional bargaining unit for Graduate Assistants.

The only direct cost of AB 191 is the fee to support the EMRB. That fee is up to $10 per year per bargaining unit member, so the fee will be roughly up to $8700 per year until additional bargaining units are established. The actual EMRB assessment for State Classified employees is currently $4.25/year, well below the $10 statutory maximum. The EMRB fees would be offset by savings on resolution of bargaining unit, contract, or negotiation issues by the EMRB that would otherwise go to voluntary private arbitration or to litigation.

The costs of arbitrations for grievances will likewise be more than offset by savings from avoided litigation. While NSHE's fiscal note on AB 224 in 2023 projected 200 to 800 binding arbitrations for grievance appeals each fiscal year, the 2025 fiscal note indicates their are only 17 grievances last year statewide that escalated to a president or the chancellor. Even if all of those were appealed to an arbitrator, the cost at NSHE's (high) estimate of $5600 each in the fiscal note would be $95,200 split between NSHE and NFA. Much more is being spent by NSHE on litigation, both with internal general counsel and on outside counsel, that could be avoided through arbitration.

Does AB 191 require binding arbitration for all grievances?

No, that is a misrepresentation or misunderstanding. AB 191 allows arbitration as the final level of appeal of a grievance that is not resolved at lower levels. Collective bargaining agreements negotiated under AB 191 would provide for binding resolution by an independent arbitrator of final appeals, but it would only apply to members of bargaining units with a collective bargaining agreement. Arbitration avoids expensive litigation, a cost savings to NSHE which regularly hires outside counsel to handle lawsuits over personnel issues. Collective bargaining agreements can provide better methods for resolving workplace disputes; for example, TMCC has been able to reduce the frequency of grievances through provisions for informal resolution in its collective bargaining agreement.

Does AB 191 expand what is grievable in comparison to the NSHE Handbook?

Yes, but only once a collective bargaining agreement is established for a particular employee group. The scope of grievances for faculty in Title 2 Chapter 5 is narrowly defined and does not encompass the standard definition of grievances NSHE classified employees in bargaining units currently have. There is no grievance policy in the Handbook for graduate assistants or other non-faculty professional employees. AB 191 provides the same foundation for all employees.

How many grievances will go to arbitration?

In 2023, NSHE claimed AB 224, the nearly identical predecessor of AB 191, would lead to hundreds of arbitrations over grievances. If that were the case, it would just show a dire need for collective bargaining to improve working conditions for professional employees at NSHE. In the fiscal note for AB 191, NSHE reports that last year there actually were only 17 grievances statewide that were denied by Presidents, the final level of decision under NSHE Code. Those would be eligible for appeal to arbitration under AB 191. To our information and belief, since collective bargaining agreements for Classified employees have been in place after 2021, only one grievance for a Classified employee at NSHE has gone to arbitration.

Does AB 191 allow NSHE professional employees to strike?

No, NRS 288 has strong prohibitions against strikes by public employees in Nevada, and AB 191 does not change that.

Does AB 191 change Nevada as a Right to Work state?

No. Right to Work means that employees are not required to join a union or pay dues to receive the benefits of collective bargaining. Employees cannot be forced to join a union as a requirement of employment. That will not change with AB 191.

What happens in case of an impasse in the negotiation of a collective bargaining unit?

Under T4C4, there is a mediation and advisory fact-finding process but management is not required to accept the recommendation of the independent fact-finder. That means negotiations can drag out for a long time–the first contract at CSN took years to negotiate. Under AB 191, which follows the same process as in NRS 288 for state Classified employees, an impasse first goes to mediation and then binding arbitration under strict timelines. The arbitrator is required to choose the more reasonable proposal from the two parties based on stated criteria, and is not allowed to modify the chosen proposal. That forces both parties to make final proposals that are reasonable, not ask for exaggerated provisions hoping the arbitrator will split the difference. The two parties can extend the times for negotiation, mediation, and arbitration only by mutual agreement.

Would AB 191 cover Unclassified or Nonclassified employees in state agencies outside of NSHE?

No. The definitions of “professional employee” and “state professional employer” in AB 191 effectively limit its applicability to NSHE.

Would the Labor Relations Unit in the state Division of Human Resource Management negotiate with professional employee associations on behalf of NSHE?

No. AB 191 both authorizes and requires NSHE to conduct its own labor relations and collective bargaining negotiations with its professional employee bargaining units. NSHE could choose to use the services of the DHRM or the Office of the Attorney General for labor relations, but those entities could charge NSHE for any such service.

Are the rights reserved to management restricted by AB 191?

AB 191 recognizes the principles of shared governance, which is a good thing. Academic freedom means that the determination of the “means and methods” of delivering education and research are the responsibility of teachers and scholars, not management. Personnel decisions in academia involve peer review. More expansive management rights for a governmental agency such as the DMV or Corrections, for example, for absolute control over staffing and services would not be appropriate for institutions of higher education.

Does AB 191 extend collective bargaining to “at will” employees such as Unclassified and Nonclassified employees in state government?

The Unclassified and Nonclassified employees in other state agencies are political appointees and upper management. As “managerial” or “confidential” employees, most if not all would be ineligible to collectively bargain under AB191 if the bill included those agencies among “state professional employers”, which it doesn’t.

NSHE suggested that graduate assistants are “at-will” as a means to justify their current exclusion from T4C4 and implied that NSHE might oppose AB 191 because it includes graduate assistants. However, in practice, having any due process for termination (as we have with most NSHE employees, including graduate assistants) demonstrates exceptions to a position where “at-will” means firing anyone at any time. Collective bargaining allows for termination procedures to be standardized and negotiated with recourse for violations of them.

For further information contact: Kent Ervin, kent.ervin@nevadafacultyalliance.org

Updated 3/28 with additional information about fiscal impact and effect on tenured or grant-funded faculty.

Updated 4/6/2025 to recognize the successful bargaining unit election at NSU.

Updated 4/18/2025 with current legislative status and other clarifications.

Updated 4/23/2025 with a discussion of whether current state law allows NSHE to voluntarily recognize and bargain with profession employee associations.

Updated 4/27/2025 to indicate that there are five employee associations representing the 12 state Classified bargaining units.